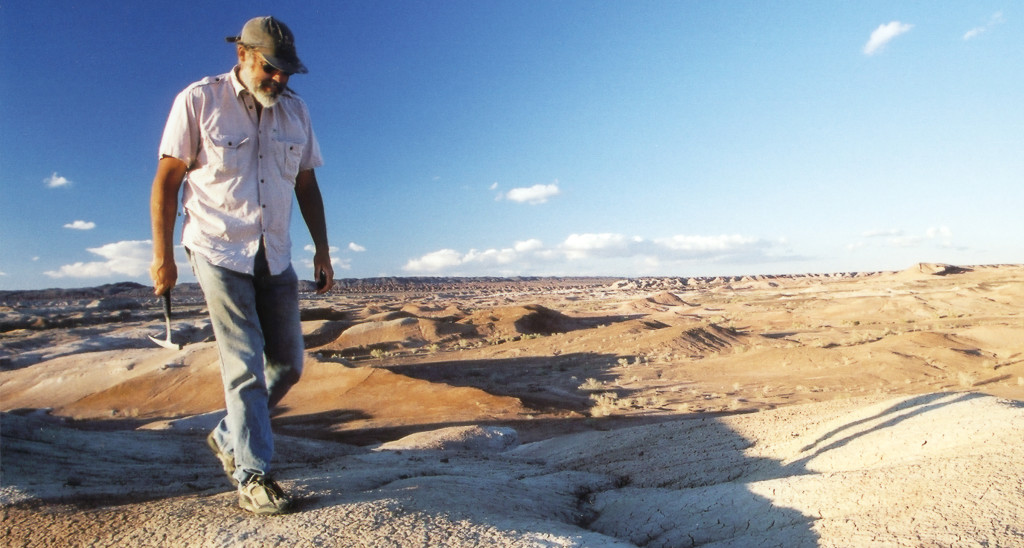

Jim Clark treks across the desert for weeks at a time. Slowly, methodically, he makes his way over the rocky terrain that was once a lush area home to a myriad of prehistoric wildlife long since gone. Not many people will say they love the desert, but not many people are paleontologists and evolutionary biologists like Professor Clark. Hidden among the thick sequences of rocks are pieces to an evolutionary puzzle, and the barren expanse offers the perfect backdrop for the GW professor’s search.

“Sometimes you are only able to see the tiniest bit of bone in the rocks, but you have to be able to see the rocks clearly; you can’t have any plants covering them,” says Clark, who is the Ronald B. Weintraub Professor of Biology Systematics at GW. “Many of the best fossil beds are in the desert, and I just really, really enjoy digging there. I love it out there.”

After more than 30 years, Professor Clark still gets excited about being in the field. Each expedition brings new expectations about what discoveries might be made. Some sites yield finds every day or two, but others he will search for weeks at a time without any results.

“When you’re looking for fossils out there, you put your lunch in your bag and grab your water and you head out and you just walk all day long,” he says. “You walk for miles and miles and miles, and you can go days without seeing anything. But then every once in a while you see little pieces of bone coming out of the rock and you dig in and it gets very exciting. It’s an incredible experience.”

Fieldwork Tech

Once fossils are found, the techniques used to remove them from the rocks they’ve called home for the past few million years can be fairly sophisticated—acids, mechanical extraction, and density separation via liquids are just some of the methods employed—but locating the fossils is surprisingly low tech.

Yes, there are satellite images and GPS and even ground-penetrating radar, but nobody uses that with any regularity, says Professor Clark. “It’s all about getting your feet out in the field and looking at as much rock as you can.” Like so many things, sometimes the simplest way is the best one.

Over the years, those little pieces of bone have yielded big finds for Professor Clark—he has discovered nearly 40 different species of extinct land vertebrates (tetrapods) from the Age of Dinosaurs. These discoveries have spanned four continents and include dinosaurs, turtles, ancient reptiles, and mammal-like creatures, but recently Professor Clark and his team have focused their search on the time period where they expect to find the dinosaurs that gave rise to birds.

A paleontological theory for decades, the connection between dinosaurs and birds wasn’t fully realized until fossil beds of theropod dinosaurs (including tyrannosaurs and velociraptors) with feathers were discovered in the last 20 years.

“These theropod dinosaurs are just what you would expect for the ancestors of birds,” Professor Clark says. “There were all different kinds of feathers, and that was just a huge leap in our knowledge about those things.”

“These theropod dinosaurs are just what you would expect for the ancestors of birds,” Professor Clark says. “There were all different kinds of feathers, and that was just a huge leap in our knowledge about those things.”

The connection was clear, but the thousands of little evolutionary steps from dinosaurs to birds as we know them today largely remain a mystery. Each new fossil find, however, brings with it the possibility of new understanding.

“We know that birds evolved from dinosaurs, but exactly where they fit in as part of the larger evolutionary picture is a big question,” Professor Clark says. “How these theropod dinosaurs evolved right before they became birds is a really interesting question, so we target the fossil beds of that age with the hope that new discoveries will shed some light on that.

“We are looking for patterns of evolution, looking at the fossil records and asking, ‘What were the changes and at what point did these changes take place?’ Everything that’s distinctive about birds you go back to the fossil records and try to zero in on where that occurred. Everything evolved, every species has a history, and we’re just trying to get a better understanding of that history.”

Professor Clark’s own history with fossils dates back to his days as a middle-schooler in Southern California. On weekends, he participated in a program at the Natural History Museum of L.A. County that allowed him to take classes from the museum’s curators and even volunteer with the museum lab’s fossil preparer.

“For me, hanging out with curators who were paid to go out and collect fossils and study them and explain them to the public, to just see that career existed, was a big deal,” he says. “That’s definitely when the seed of becoming a paleontologist was planted.”

The summer after his first year at California State University, Long Beach, Professor Clark got his first taste of being out in the field when a professor (a vertebrate paleontologist) invited him to participate in that season’s fieldwork. Professor Clark spent that summer on an expedition in Colorado and was part of discovering a dinosaur fossil site that would become well-known among paleontologists.

“That was a really great opportunity, and it really reinforced my interest in paleontology,” he says.

Every summer after that, Professor Clark returned with his professor, George Callison, to continue digging at the same site, even after transferring to UC Berkeley, the top paleontology program in the western U.S., where he earned bachelors’ and masters’ degrees.

Every summer after that, Professor Clark returned with his professor, George Callison, to continue digging at the same site, even after transferring to UC Berkeley, the top paleontology program in the western U.S., where he earned bachelors’ and masters’ degrees.

After completing his PhD in anatomy at the University of Chicago, Professor Clark travelled first to UC Davis to learn molecular evolutionary techniques, then back east to work for the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., before joining the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, where he took part in a series of extremely successful and widely publicized expeditions to Mongolia. A few years later, he was drawn back to the nation’s capital by a position on GW’s faculty: the Ronald B. Weintraub Professorship of Biology Systematics.

“It’s been 21 years, and I’m part of the old guard here at GW now,” he says with a smile. “I’ve served as the Weintraub Professor since the beginning.”

The Ronald B. Weintraub Professorship is one of five biology faculty positions endowed in GW’s Columbian College of Arts and Sciences by the late Robert L. Weintraub, BS ’31, MA ’33, PhD ’38, and his wife, Frances Weintraub, MA ’33. A biochemist and plant physiologist, Dr. Weintraub was a long-time member of GW’s faculty and chair of the biology department who was awarded the status of Professor Emeritus of Botany upon his retirement in 1977.

Each of the endowed faculty positions established by the Weintraub Professorship Fund is named in honor of a member of the Weintraub family or an influential person in their lives. The Ronald B. Weintraub professorship is named for Robert Weintraub’s late son.

Dimorphodon Weintraubi

In February of 1998, the foot fossil of a newly discovered species of pterosaur, a group of winged reptiles closely related to dinosaurs, graced the cover of Nature magazine. The foot—whose structure contradicted a previous reconstruction of pterosaurs—belonged to a set of fossils discovered by Professor Clark which he named for Robert L. Weintraub.

“I was, and still am, so grateful to hold this position,” Professor Clark says, “and I felt this was a way for me to pay tribute to the impact Robert L. Weintraub has had on our department and the generosity and foresight he and his wife demonstrated in establishing this wonderful faculty position.”

“The Ronald B. Weintraub Professorship of Biology Systematics is definitely what brought me to GW,” Professor Clark says. “It’s a great, research-oriented position that provided me the flexibility to conduct more fieldwork that’s really essential to our research. All the Weintraub professorships are very desirable positions, and we’ve been able to attract some really talented researchers to our faculty.”

The flexibility to conduct more field research provided by the Weintraub Professorship has allowed Professor Clark to attract some of the best and brightest young paleontologists to his lab at GW over the years, too.

“When grad students are looking for a place to go, having new fossils for them to study is something that gives you an advantage over other grad programs,” he says. “I think the point for us as professors is to provide students with the opportunity to do some truly interesting and meaningful research and help guide them the best we can.”

Professor Clark’s expertise and fieldwork is what brought PhD candidate Josef Stiegler to GW in 2010. Josef has spent the last five years working with Professor Clark, participating in expeditions to Utah, Inner Mongolia, and Xinjiang, China. His dissertation focuses on the Limusaurus inextricabilis, a dinosaur discovered by one of Professor Clark’s expeditions in Xinjiang.

Professor Clark’s expertise and fieldwork is what brought PhD candidate Josef Stiegler to GW in 2010. Josef has spent the last five years working with Professor Clark, participating in expeditions to Utah, Inner Mongolia, and Xinjiang, China. His dissertation focuses on the Limusaurus inextricabilis, a dinosaur discovered by one of Professor Clark’s expeditions in Xinjiang.

Josef says he and Professor Clark have worked closely together on the dissertation, but that his graduate advisor also provides his students with the freedom to follow their own research interests.

“My research is moving in the direction of understanding the relationship between the evolution of dinosaurs and the sometimes radical environmental changes during the Mesozoic Era,” Josef says. “This is not an area that Jim’s research has been focused on, but he has encouraged me to pursue it.”

Jonah Choiniere, PhD ’10, one of Professor Clark’s former students, remembers the generosity with which Professor Clark treated him, serving as a mentor, collaborator, and friend.

“Jim opened the door to fantastic research opportunities for me in China, at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, and across the world as a visiting scholar at paleontological collections,” says Dr. Choiniere, who is now the senior researcher in Dinosaur Paleontology at the Evolutionary Studies Institute of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa.

“Together with his wife, Cathy Forster, who is also a GW faculty member, Professor Clark set me firmly on the path that led to my career as a dinosaur researcher.”

Recognizing the impact that being able to conduct fieldwork as an undergraduate had on his own career, Professor Clark has strived to provide his graduate students with similar experiences by giving them the tools and opportunities to make their own marks in the field.

“Working with grad students is a big part of my job, and that’s why I’ve developed some of the projects I have,” he says. “My job as a professor is to train these students and to provide them the chance to do great work of their own.”

Although he sees his role as teacher and mentor as an important one, Professor Clark isn’t passing the torch altogether—there are still questions he hopes to answer.

“There are a lot of fossils that have yet to be discovered,” he says. “There’s a lot that we can still learn out there.”